The Net Benefits of Haven for Hope

Haven for Hope began operations in 2010 with the mission “to offer a place of hope and new beginnings by providing, coordinating, and delivering an efficient system of care for people experiencing homelessness in San Antonio.” Haven for Hope has become a model of excellence for how to establish and operate a facility to effectively and efficiently serve those who are experiencing homelessness. With its 75 partners and numerous volunteers,[1] Haven for Hope has provided care for 52,108[2] people who have experienced homelessness with profound impacts on their lives and the broader San Antonio and Bexar County community. For example, after one year upon graduating from Haven for Hope, 92.42 percent of those who exited to housing in 2023 remained in housing for at least twelve months through 2024. The retention rate for all of those who exited Haven for Hope and remained out of homelessness for at least twelve months, including those who exited to another facility for higher care, to stay with family or friends, to a transitional housing facility, and including all those who exited without completing an exit interview was 75.01 percent as of 2023. In part, this high housing retention rate is the result of the fact that 683 clients of Haven for Hope in 2024 found employment.[3]

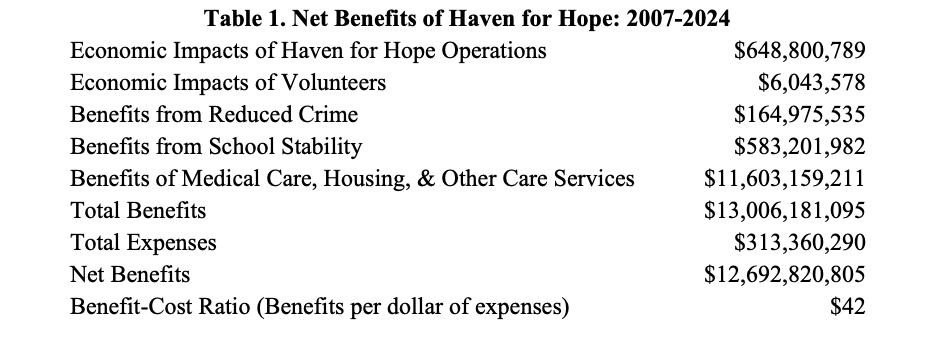

I recently completed a study to measure the net benefits of the services provided by Haven for Hope to the community from 2007 through 2024.[4] The value of the benefits and total expenses measured in the study are provided in the following table. Haven for Hope has provided net benefits to the community of $12.7 billion. In other words, for each dollar spent to create and operate Haven for Hope, the community has received $42 in benefits.

While the scope of this study only analyzed the benefits through 2024, it is also worth noting that Haven for Hope has continued to innovate and push its model of excellence in serving persons experiencing homelessness and the broader San Antonio community. This is exemplified through its contributions to the community’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. While much of the community was in lockdown and experiencing unprecedented economic stress due to the pandemic, Haven for Hope made numerous adaptations to their operations in order to keep safely providing their services. This included the creation and implementation of Operation Hope Away from Haven focused on serving their highest-risk clients who had become exposed to COVID-19 and to maintain social distancing.

As these results indicate, Haven for Hope’s impact on the San Antonio community has been profound, especially for those they serve, but their overwhelmingly positive impacts extend well into the broader community. By providing a path to a new beginning for those who are experiencing homelessness, Haven for Hope’s work towards the achievement of their mission contributes substantially to both the quality of life of those they serve and all who live in San Antonio and Bexar County. By helping those persons experiencing homelessness find permanent housing and providing them with the care, guidance, and skills each individual needs to begin a successful journey to self-sufficiency, these benefits will be felt throughout their lifetimes and will also serve as a catalyst for economic development well into the future.

In the full report, the methodologies used in the analysis are documented and more detailed results are provided. If you wish to read the report, you can find it at this link.

[1] Source: https://www.havenforhope.org/our-partners/

[2] Data provided by Haven for Hope.

[3] Data provided by Haven for Hope.

[4] While operations did not begin until 2010, expenses to establish Haven for Hope began in 2007, so while the benefits were measured from 2010 through 2024, the expenses were calculated going back to 2007.